4Cold War and decolonisation (1944-1968)

The decades after the war were marked by the Cold War and characterised by expansion of the Olympic movement towards Oceania, then Asia and Latin America. Despite the IOC’s stated desire for neutrality, the Olympic Games formed a space for geopolitical confrontations, as well as political and social demands from oppressed minorities. Versions of the Olympic model multiplied, in particular promoting better recognition for athletes with disabilities.

In 1948, the London Games celebrated the British and American democracies. Four years later in Helsinki, the USSR took part in the Games for the first time, transforming the event into a new Cold War front. In 1956, the USSR’s repression of the revolt in Budapest was an unexpected guest at the Melbourne Games when a fight broke out between Russian and Hungarian athletes.

In the 1960s, the Olympic Games held in Rome (1960) and Tokyo (1964) were a sign of renewal inside the host countries. For Italy, it was about forgetting fascism, and for Japan, haunted by the atomic bombings, defeat. These two events reflected the movement towards decolonisation, and hosted the first delegations from newly independent African countries. The 1968 Games in Mexico were an echo chamber for the struggles of youth around the world. One image dominated: on the 200 metres podium, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their black-gloved fists to support the civil rights movement in the United States.

Rebuilding Europe, restoring Olympism

Legende

View of the rooms in the exhibition Olympism, a world history

Credit

© EPPPD-MNHI

The members of the IOC voted unanimously in favour of London to host the 1948 Games. A symbol of European resistance to Nazism, the English capital was being rebuilt. Despite the uncomfortable lodgings and food rationing, the Olympic movement got back in touch with its values and optimism. The broadcast of the event was key to its success. BBC cameras gave 500,000 television viewers the chance to follow the events live. Several former British colonies that were newly independent took part in the Olympic Games for the first time. This was the case with India, winning the gold medal for field hockey, as well as Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Jamaica - still part of the Empire – also presented a delegation.

The United States, a major sporting power

Composed of 332 athletes at the London Olympic Games, the American delegation finished at the top of the nations’ rankings with 84 medals, of which 38 were gold, well out in front of Sweden with 44 medals and France in third place. This crushing domination, in particular in athletics, swimming and weightlifting, reflected a dynamic country that was imposing itself as a hegemonic power from a military, economic and cultural standpoint since the end of the war.

Two exceptional champions

Dutch athlete Fanny Blankers-Koen and French athlete Micheline Ostermeyer gave illustrious performances and had outstanding personalities. Fanny Blankers-Koen took a record four gold medals in athletics (80 metres hurdles, 100 metres, 4x100 metres, 200 metres). Micheline Ostermeyer was victorious in the shot put and the discus. A rarity at the time, Fanny Blankers-Koen was both an athlete and mother to two children, which earned her the nickname “the flying housewife”, while Micheline Ostermeyer had a parallel career as a pianist.Alfred Nakache, Jew, deportee, hero

In November 1943, Alfred Nakache, a French swimming champion who took part in the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936, was arrested by the Gestapo. An Algerian Jew who was stripped of his French nationality by the Vichy government, he and his wife were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. The only survivor, he returned to France in 1945. Displaying unrivalled persistence, he returned to his best form and was chosen for the London Olympic Games to compete in the 200 metres breaststroke and on the water polo team.

Games under the sign of the Cold War

When the organisation of the Olympic Games was entrusted to Helsinki in 1947, the Finnish capital had been preparing to host the event for over ten years. The Olympic stadium had in fact been built for the Games that were cancelled in 1940. While the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War intensified, the Games were held in a neutral country. Tsarist Russia had taken part in the 1912 Olympiad, but it was the first time that Communist USSR sent athletes to the Games, which was a boon for the IOC as interest in the competition continued to grow. Communist delegations were housed in an Olympic Village apart from the other participants. The USSR took second place on the podium, just behind the rival American team: this was the beginning of a merciless East/West sporting confrontation.

Legende

View of the rooms in the exhibition Olympism, a world history

Credit

© EPPPD-MNHI

Emil Zátopek, the Czech locomotive

In Helsinki, Czechoslovakian soldier Emil Zátopek accomplished an achievement that has never been equalled by winning the 5,000 metres, the 10,000 metres and the marathon. This success led to his promotion to Commander, reinforcing his huge popularity on both sides of the iron curtain. In the West, he was admired for his human qualities and physical capacity. In the East, he embodied the values of effort, work and organisation dear to the Communist regimes. From their point of view, his victories confirmed the efficiency of the Soviet model.

Team USSR and the new Soviet sports strategy.

With 71 medals, the USSR were hot on the heels of the United States at the Helsinki Olympic Games. Discus thrower Nina Romashkova was the first Soviet gold medal-winner, and symbol of a USSR with ambitions to demonstrate world dominance through sport. It was also about conveying a good image of the “homo sovieticus” as seen in the scenes of fraternisation between the Soviet athlete Petro Denisenko and American Bob Richards in the pole vault, or the gifts exchanged between oarsmen from both countries.

The first southern hemisphere Games

In 1956, the original location for the event forced the organisers to adapt the format of the competition. Equestrian events were dissociated and moved to Sweden to avoid horses being placed in quarantine, which was mandatory in Australia. In addition to this, because the seasons are inverted between the two hemispheres, the Games were held from 22 November to 8 December. Before a home crowd, the Australian team shone, led by the exploits of the sprinter Betty Cuthbert who won three titles, and took third place in the overall rankings. International tensions, in particular the repression in satellite USSR States, led the organising committee to transform the closing ceremony into a parade with no national distinctions, to offer a more utopian vision of world unity.

Hungary-USSR confrontation

In autumn 1956, Budapest was invaded by Soviet tanks sent in to put down a popular revolt against the Hungarian Communist regime. The conflict wound its way to Melbourne, where the water polo semi-final opposing the USSR and Hungary turned into a “bloodbath” after a fight broke out and put an end to the match. After the Games, 45 athletes, including the quadruple Olympic gymnastics champion Ágnes Keleti, decided not to return to Hungary and were granted political asylum in Australia.

The reunified German team

In 1949, the division of Germany into two States led to the creation of two separate national Olympics committees. Nevertheless, the president of the IOC wanted to keep German athletes under a single flag composed of three bands, black, red and gold, with the Olympic rings acting as a coat of arms. The victories were celebrated by the Ode to Joy and not by national anthems. It was not until the 1968 Olympics that the FRG and GDR split into two delegations.

Legende

Melbourne 1956. Erwin Zador, Hungarian water polo player, injured in the "Melbourne bloodbath".

Credit

© Public Record Office Melbourne

Melbourne 1956. Alain Mimoun wins the marathon.

© Docpix

Alain Mimoun, marathon winner

In Melbourne, the French athlete Alain Mimoun took part in the Olympic Games for the third time. The preceding Games had been the theatre of a stirring sporting rivalry between the Czech Emil Zátopek, forcing the Algerian born runner to settle for the silver medal on three occasions. The man from Oran, who had enlisted in 1939 in a regiment of Algerian tirailleurs in the French army, won the marathon in 1956 after a gruelling race, earning himself the status of a national hero in Australia.

Forgetting fascism?

The Olympic Games of the XVII Olympiad held in Rome revealed an image, widely covered by television, of a host country in equal parts rooted in its past heritage and supported by the vitality of its “economic miracle”. Events took place at ancient sites, and the modernity was embodied by new sports facilities. While the vocation of the Games was to celebrate Italy’s return to democracy, the traces of fascism and its imperialist ambitions were hard to erase. The Olympic stadium reigned over a complex built by Mussolini with the goal of forging the bodies of the fascist “new man”. The architecture, the statues and the inscriptions glorifying fascism formed an environment that was at odds with Italy’s contemporary aspirations.

An imperial victory

A soldier of the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie’s guard, Abebe Bikila, who had never taken part in an international competition, was sent to the Games after one of his countrymen dropped out due to injury. To everyone’s surprise he won the marathon, running barefoot. He crossed the finish line under the Constantine Arch, where Benito Mussolini had declared war on Ethiopia in 1935. This first Olympic medal for an independent African State felt like a form of revenge over colonial domination.

First Paralympic Games

One week after the Olympic Games, the ninth Stoke Mandeville Games brought together 400 athletes with disabilities from 23 delegations, in eight events. Created by German doctor Ludwig Guttmann, these games had been held since 1948. In Rome, they were held for the first time in an Olympic setting, a principle that continues to this day. In the 1980s, with the creation of official paralympic bodies, this would come to be recognised as the first Paralympic Games.

Legende

Rome 1960. Ethiopia's Abebe Bikila, first black African Olympic champion

Credit

© Docpix

Mohamed Ali : birth of an icon

Already a title-holder in the United Sates, boxer Cassius Clay was confident on his arrival in Rome. Under the dome of the Palazzo dello Sport, he won the gold medal in front of 16,000 spectators. Celebrated around the world, he joined the professional circuit and could no longer take part in the Games. He converted to Islam in 1964 and took the name Muhammad Ali. He put his fame to work serving political combats for equal rights for African-Americans.)

A new Japan

The Tokyo Olympic Games were the first to be held in Asia. Defeated in the Second World War, Japan intended to show its economic strength, third in the world, and rehabilitate its international image. The choice of the last torch-bearer to be Yoshinori Sakai was highly symbolic, because the athlete was born on 6 August 1945, the day on which Hiroshima was bombed by the United States. Colossal investments were made to host the Games. The programme of events included judo, an emblematic sport in Japanese culture. Winning three out of four titles in this discipline, and flushed with success in wrestling, gymnastics or the newly introduced volleyball, Japan took third place on the Olympics medal table.

Africa, Olympic force

The pace of decolonisation had quickened since the end of the Second World War, leading to the recognition of new national Olympic committees. Fourteen countries that had recently become independent, mainly African nations, were represented in Tokyo. Ghana, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Tunisia all won medals. The influence of Africa could be felt in the process that led to the exclusion in 1963, just before the Olympic Games, of South Africa, which was governed by the racist apartheid regime.

Ganefo (Games of the New Emerging Forces), multi-sport competition to counter the Olympic Games

© Docpix

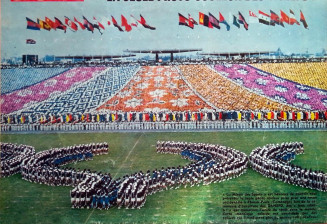

Counter Games for emerging nations

The Games of New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) were a competition created by so-called “emerging” nations that were not aligned along East and West blocs, as seen with the Bandung agreements of 1955 between States that refused the Cold War logic. In 1963, in Indonesia, they brought together 51 countries, including the USSR and China, as the latter had not taken part in the Olympic Games after 1952. Under pressure from the IOC, Western countries and international federations, the GANEFO rapidly declined.

1968, revolts and repressions

The world was rocked by multiple protest movements led by young people in France, Japan, the United States and in the host country of the Games. By choosing an “emerging” nation, the IOC wanted to prove that the Games were universal. However, at that time, Mexico was in the grip of a violent dictatorship. In vain, voices attempted to speak out in favour of a boycott. Ten days before the opening ceremony, a student and workers’ demonstration was violently put down, leading to international outcry. So, in a falsely festive atmosphere and a ceremony under strict army surveillance, Enriqueta Basilio, a Mexican athlete, became the first woman to light the cauldron of the Olympic Games with the slogan “Everything is possible in peace”.

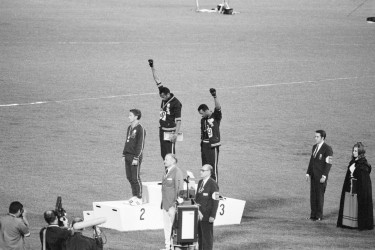

Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the struggle against racial discrimination

In the United States, racial segregation officially ended between 1956 and 1968, but discrimination towards African-Americans persisted. On the 200 metre podium, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists, in reference to the Black Panther movement fighting for racial equality. They were suspended by the American Olympic committee and banned from the Games. On the second step of the podium, the Australian athlete Peter Norman wore a badge marked “Human Olympic Project for Rights”. The show of support also displeased the Australian committee, which excluded him from future competitions.

Legende

Mexico City Olympic Games (1968) - On the 200m podium, American athletes Tommie Smith (gold medal) and John Carlos (bronze medal) raise a black-gloved fist in reference to the Black Panther Party, which fights for racial equality in the USA. In a show of solidarity, Australian Peter Norman (silver medal) wore an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge.

Credit

© Getty Images

Inclusive Olympics

Eunice Shriver, a member of the Kennedy family, created the first organisation for realisation through sport for people living with a mental disability, particularly children. The first Special Olympics competition was held in Chicago in 1968. One of the major figures of the movement was the African-American athlete Loretta Claiborne. Now present in 172 countries, the Special Olympics bring together more than 5 million athletes and are recognised by the IOC.