2The (re)birth of Olympism (1896-1919)

Pierre de Coubertin was behind the renaissance of the ancient Olympic Games and the creation of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), founded on 23 June 1894. The goal of the IOC is to promote young people’s physical education and sporting universalism to serve peace. The original choice of amateur athletes reflects the aristocratic elitism behind the project, restricting the participation of athletes from the working classes.

The first Olympic Games held in Athens in 1896 were popular with a wide public. This success was promoted by the involvement of the Greek royal family who wanted to assert Greece’s position on the European stage. The next three Games in Paris (1900), then on the other side of the Atlantic in St. Louis (1904) and finally in London (1908) were diluted within the programme of major universal or international exhibitions. Despite this confusion, the successive organising committees gradually laid the foundations of a universal Olympic project that initially excluded women, and then restricted their participation to a limited number of events. In 1912, the first truly independent Games were held in Stockholm, in Sweden. Delegations arrived from the five continents to take part.

The start of the First World War led to the cancellation of the 1916 Games planned for Berlin. The dream of a competition capable of rising above conflicts appeared to collapse.

“The first games”

Legende

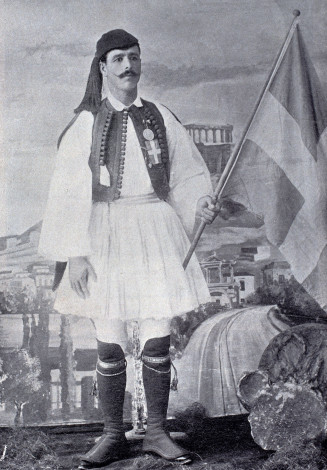

Spyridon Louis in traditional costume. He became the first Olympic marathon champion at the Athens Olympic Games in 1896.

Credit

© Docpix

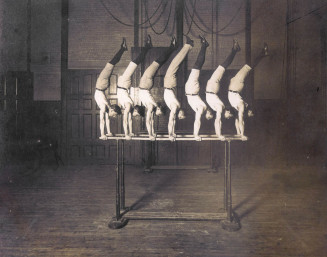

Hosting the first modern Games was perceived by the Greek monarchy as an exceptional opportunity for national self-assertion. On 6 April 1896, King George I launched the competition in the ancient Panathenaic Stadium renovated for the occasion. 241 competitors from fourteen nations, all men, competed in 43 events. The cost of travel and the absence of national Olympic committees led to low participation from non Greek athletes. The Hungarian athletes were the only ones to receive government funding for the trip. Among them, young Alfréd Hajós won two Olympic titles at swimming events held in the Aegean Sea. Some political tensions were revealed on the sports field, such as the rivalry between French and German gymnasts.

Spyrídon Loúis (1873-1940), hero of the marathon

On 10 April 1896, the Greek shepherd Spyrídon Loúis won the so-called “Marathon” race. The event was invented by the linguist Michel Bréal to revive the legend of the path taken by the messenger Philippides from Marathon to Athens in the 5th century B.C. The victory also served the ambition of the young Greek nation that had been independent since 1830 for international recognition. When he received his award, Spyrídon Loúis wore a fustanella, the traditional skirt that symbolised the national identity.

“The Olympic Games at a time of technical and industrial modernity”

Since 1894, the artisans of the Olympic rebirth had pictured the second Games being held in Paris, as part of the Universal Exposition of 1900. This spectacular event lasting six months elevated the French capital as a beacon of worldwide technical and artistic modernity. It attracted 50 million visitors, guaranteeing popular success for the Olympiads. However, the elitist Coubertin model of the wealthy amateur sportsman clashed with the Republican ideals of Alfred Picard, the Commissioner-General of the fair. He chose to exclude the IOC from the organising committee and preferred to hold an “international physical exercises and sports competition” that was democratic and patriotic. The many events, some of them comical, were spread out over space and time, and brought together nearly 60,000 participants.

Legende

View of the rooms in the exhibition Olympism, a world history

Credit

© Palais de la Porte Dorée

Quirky sports

The 1900 Olympic Games highlighted several sports that seem quirky to us today, such as tug-of-war, line fishing or live pigeon shooting. Some events revived ancient practices. Others sought modernity and delighted a public avid for sensationalism. Hot air balloon races were organised: the distance one took the winner to Kiev, while the altitude one put the participants in danger.

Constantin Henriquez, champion olympique haïtien et français

In October 1900, two victories over Germany and England offered the French rugby team victory as Olympic champions. Constantin Henriquez, a Haitian student of medicine, arrived in Paris in 1893 and became the first African-Caribbean medal-winner. The presence of this Stade Français player on the French team was made possible in the absence of rules regarding athletes’ nationalities. On his return to Haiti in 1906, Constantin Henriquez became the country’s first Olympic Committee president.

The first female Olympians

Only around forty women took part in the games at exclusively female tennis, sailing, croquet, equestrianism and golf events. On 11 July 1900, the British tennis player Charlotte Cooper become the first female Olympic champion. The fledgling feminisation would remain limited and continued to cause reluctance. Promotional posters for fencing competitions were misleading, because the discipline, like many others, remained exclusively masculine.

“An American Olympiad”

In order to confirm the international dimension of the Olympic Games, the IOC wanted to hold the third competition on the other side of the Atlantic. The city of St. Louis was chosen against the wishes of Pierre de Coubertin, and once again integrated the event as part of the programme of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. These Games recorded the lowest turnout of athletes in history. The absence of several delegations that were unable to finance the trip offered the United States a broad victory, awakening the national sporting consciousness. The St. Louis Games also reassured white American society in its racialist and hierarchical conception of the world, in particular because of the “Anthropology Days” that were organised in which supposed “savages” competed in sporting contests.

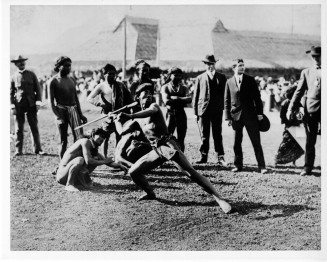

The Anthropology Days

The Anthropological Days aimed to demonstrate the superiority of the “white race” over so-called “savages”. Without any training for events for which they were not aware of the rules, the natives were exhibited as part of the Universal Exposition and their performances were poor. The young Pygmy Mbuti Ota Benga, kidnapped in the Congo in 1904, was one of them. He went back on display in New York Zoo after the Games in 1906, then committed suicide when he despaired of ever returning to Africa.

Legende

Jessie Tarbox Beals. Javelin throw at the Anthropological Games: an Igorot competitor (Philippines). 1904

Credit

© St. Louis Public Library

One-legged gymnast Georges Eyser (USA, center), the first disabled athlete in the history of the Games. Photographed by Louis Melsheimer, 1904. Photographic reproduction

© Missouri Historical Society

Albert Corey and George Eyser, United States immigrants

Frenchman Albert Corey and German George Eyser emigrated to the United States along with millions of other Europeans. Although a recent arrival, Albert Corey, originally from the Franche-Comté region, won the silver medal in the marathon under American nationality. His medal was only “returned” to France in 2021. George Eyser, a leg amputee following a train accident, competed with able athletes and won six medals for gymnastics, including three gold.

“The Games to serve the Entente Cordiale”

In 1906, the eruption of Vesuvius threw Italy into a serious economic crisis. Originally awarded to Rome, the organisation of the 1908 Games was finally entrusted to London. The competition was integrated to the Franco-British Exhibition that lavishly celebrated the Entente Cordiale between the two countries. The British Olympics Association came up with a version that was less dispersed than the previous ones. The White City Stadium built for the occasion hosted the first parade of nations. During the opening day, there were also sports demonstrations, including a bicycle polo match. While the suffragette movement to promote voting rights for women drew crowds to the heart of London, women’s participation remained restricted to just skating, tennis, sailing and archery events.

The first African and African-American champions

In 1908, the British colonies of South Africa took part in the Olympic Games for the first time. The delegation did not include any black or mixed-race athletes. By winning the 100 metres sprint, Reggie Walker became the first Olympic champion to come from the African continent. Three days later, the American team won the relay with John Taylor on the team, the first African-American athlete to represent the United States in an international competition.

Legende

London 1908. John Taylor (USA) and his Olympic relay teammates Nate Cartmell, Mel Sheppard and William F.Hamilton. July 1908

Credit

© Collection University Archives of Pennsylvania

Dorando Pietri, a royal marathon

At the request of the royal family, the marathon started outside Windsor Castle, thereby setting the 42.195km distance for the race, which has not changed since. The public, although not many in number over the whole competition, is estimated to have counted 2 million spectators that day. Leading at the end of the race, exhausted Italian runner Dorando Pietri needed outside assistance to cross the finish line. He was disqualified, but to make up for this he received a silver cup presented by the Queen in person.

“A model of organisation”

For the first time since 1896, the Olympic Games were not attached to an international exhibition. They were independently organised over a shorter period than previously, from July 6th to 22nd, 1912. Sweden, home to theorist and gymnast Pehr Henrik Ling, a “sporting nation” spearheading the spread of modern sports, appeared to the IOC to be the ideal host. King Gustave V, a sportsman and tennis enthusiast, rewarded the victorious athletes in person. Second in the number of titles won, Sweden ended first in the number of medals, ahead of the United States. The Europe-America duel increased interest in the event, in an international context notable for tensions that led to fears of more generalised unrest.

Legende

Stockholm 1912. Japanese delegation. For the first time, all five continents were represented at the Olympic Games.

Credit

© Docpix

The first five continent Games

The universalisation of the Games made progress in Stockholm. All five continents were represented for the first time. Egypt, Iceland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Serbia and Japan appeared in the Olympic arena. Extra-European athletes shone in the swimming events that now admitted women. The 100 metres freestyle events were won by Australian Fanny Durack, and by the Hawaian surfer Duke Kahanamoku, who used the little known crawl technique.

Jim Thorpe, an American at the heart of the Games

An athlete with prodigious abilities, in 1912 Jim Thorpe became the Olympic champion in the decathlon and pentathlon. His achievement, celebrated by an entire American nation, came about twelve years before the native American populations of which he was a member were granted citizenship. The following year, the IOC took away his medals because he broke the amateur rules by taking part in baseball games for money. This sanction, which was considered to be racially motivated, was only lifted in 1983.

Legende

View of the rooms in the exhibition Olympism, a world history

Credit

© EPPPD-MNHI

"The cancelled Games”

In 1912, the organisation of the sixth Olympic Games was awarded to Berlin. The choice was intended to allow a pacifist assembly to take place, in order to prevent war in an exacerbated nationalist context in Europe. It also intended to transform the country’s sports culture, dominated by gymnastics and removed from the Anglo-Saxon competitive model. In Germany, these Games were mainly viewed as an opportunity to demonstrate the might of the Empire. The Deutsches Stadion is the symbol of this. But the Great War began on 31 July 1914, and the Olympic Games were cancelled in 1915. This was when, faced with the risk of the Germans advancing as far as Paris, Pierre de Coubertin transferred the headquarters of the IOC to Lausanne to benefit from Swiss neutrality.

In sport as in war

In the sports press, the war was compared to a “big match”. The death early in the conflict of French champion Jean Bouin, the 5,000 metre silver medal winner in 1912, strengthened the image of athletes as valorous and heroic. Sport was integrated to military preparations. Some practices were promoted, such as launching grenades, but did not encounter much success. The soldiers at the front preferred to play football as an escape from military discipline and the horror of war.

The Inter-Allied Games of 1919 in Paris

After the First World War, to celebrate the victory and seal their ties, the Allies organised the Inter-Allied Games in Paris in 1919, for military staff only, at the initiative of the United States. They took place in the new Pershing stadium, built in honour of the general who commanded the American Expeditionary Forces. Eighteen nations took part in athletics, swimming, boxing, wrestling, tennis, 15-a-side rugby, equestrian, archery, baseball and basketball events.