3Times of nationalism (1920-1944)

Between the two wars, the Olympic Games contributed to the popularity of show sports promoted by the media. They attracted more delegations and an increasingly large public, and gradually took their place as a global event with a strengthened geo-political dimension.

The tragic toll of the Great War encouraged the IOC to pursue its pacifist work. In 1920 in Antwerp, the introduction of the Olympic flag and oath symbolised the unity of nations. Nevertheless, all those who lost the First World War were excluded. The following games in Paris (1924), from which Germany was also absent, then in Amsterdam (1928), were the setting for sporting exploits achieved by athletes from every horizon, in particular those from “minorities” or colonial empires. The arrival of the first media stars shook the principle of amateurism which was still strongly defended by the IOC.

In 1932, in the middle of an economic crisis, the Los Angeles Games were noteworthy for the victories by Italian athletes held up as the ambassadors of a fascist regime. Four years later, the politicisation of the event went a step further during the Berlin Games serving Nazi propaganda. Despite the exclusion of Jewish German athletes, showing disdain for the fundamental values of Olympism, the organisation and the apparent modernity of the Berlin Games appeared to be a success for Adolf Hitler. The Second World War prevented the 1940 and 1944 Games from being held.

The Games of peace

Eight years after the Stockholm Games, the Olympic flame was revived in Antwerp, Belgium, martyr country of the First World War. These “Games of Peace” introduced a number of symbols that went on to become staples of the Olympic movement, such as releasing doves. Belgian sportsman Victor Boin took the Olympic oath, a veritable sporting code of honour, in the name of all the participants. A patriot, swimmer and fencer, he fought in the war and his versatility made him the embodiment of the amateur athlete. The Olympic flag, designed by Pierre de Coubertin, was hoisted for the first time. It had five interlocking rings against a white background, representing all the continents united by Olympism, while the colours are those of all the flags in the world.

Paavo Nurmi, the “Flying Finn”

Paavo Nurmi’s unique career began in Antwerp. The Finnish long distance runner ended second in the 5,000 metres and won the 10,000 metres, as well as the individual and team cross-country events. Thanks to rigorous and intensive training methods, he repeated those exploits four years later in Paris, where he won five medals. After the 1928 Games, the number of medals won by Paavo Nurmi amounted to twelve, and to this day he remains on the leader board of athletes who won the most medals.Suzanne Lenglen, first international star.

In 1920, Suzanne Lenglen, a young French woman aged 21, had already won Wimbledon twice. In Antwerp she won three medals, two of them gold. Her huge popularity, her determination and the care she gave to her style turned her into an icon of the Années Folles, inspiring artists and writers. Dressed by designer Jean Patou, she shook up the dress codes of the time by wearing pleated skirts that were shorter than those of her competitors.Alice Milliat and the first Women’s Games (1922)

A pioneer of feminism, Alice Milliat was an accomplished sportswoman. She was behind the first French Championship and the first French Women’s football team in 1920. She fought for women to be allowed to take part in the Olympic Games in every discipline. When the IOC refused, she first decided to hold the “Women’s Olympiad” in Monaco between 1921 and 1923, then the “Women’s Olympic Games” in Paris in August 1922, bringing together five countries in eleven disciplines.

Legende

Second Women's Olympics organized by Alice Millat in Monaco (1922) - 74m hurdles event.

Credit

Agence Rol © Bibliothèque nationale de France

Antwerp Olympic Games (1920) - American athlete Solomon "Sol" Butler, favorite in the long jump event, is injured on his first attempt.

Agence Meurisse © Bibliothèque nationale de France

Paris, world capital of Olympism

In 1924, Paris became the first city in the world to host the Games for the second time. The organising committee wanted to prove that the country was capable of this kind of large-scale organisation after the destruction caused by the First World War. They appealed to patriotism with a national subscription to complement the State and City grants. The Racing Club de France made the stadium in Colombes available. The popular success contributed to elevating France to its status as a major power. With the participation of 43 delegations including 18 from outside Europe, the Paris Games embraced world diversity a little more. In order to improve their chances of medals, the great imperial powers began to line up athletes from their colonies or ethnic minorities.

Make an event

The 1924 Olympic Games were a real success: more than 600,000 spectators thronged the stands. There were important economic benefits. Sales of derivative products such as vases, lighters, ashtrays or stamps and postcards grew, as did the number of itinerant vendors. Important media coverage was also in place with the presence of more than 1,000 journalists. The event was broadcast live on the radio for the very first time.

Johnny Weissmuller, a stateless star

Born in Freidorf in what is Romania today before emigrating to the United States, Johnny Weissmuller’s papers were not in order: he borrowed his brother’s to go to Paris. He won four medals, including three gold, notably in the 100 metres freestyle. This success allowed him to obtain American citizenship and begin a Hollywood career in which he played the role of Tarzan in a dozen films. The man who never lost a competitive race became a global star of the silver screen.

The birth of an international deaf sporting movement

The first Silent International Games were held from 10 to 17 August 1924 at the Pershing Stadium in Paris. They united nearly 150 deaf athletes representing nine countries. This competition was a tribute to the vitality of the deaf movement that became organised at the start of the 20th century, seeking to combat the stigmatising social representations of the time. Officially recognised by the IOC in 1955, these Games are now called the Deaflympics, and they are held every four years.)

Paris, world capital of diversity

Between the two World Wars, Paris was the capital of diversity. To Europeans were added colonial workers, as well as North and South Americans. Artists from all over the world came together in Montparnasse. The interest in “black culture” reached new heights: René Maran from Martinique won the Goncourt literary prize for his novel Batouala (1921), the “Bal Blomet” opened its doors (1924), and Josephine Baker triumphed in the Revue nègre (1925).

Legende

Paris, Silent Games: Paul Reinmund wins the 200-meter athletics event at the International Silent Sports Games from August 10 to 17, 1924.

Credit

© Presse Sports

Neutral games?

Held in a country that remained neutral during the First World War, during a relatively calm period on the international stage, the Amsterdam Olympic Games revealed dynamics at work inside the international sporting sphere. This is why, despite the reluctance of Pierre de Coubertin, introducing women to the Games crossed a new threshold. Women were now admitted to athletics and gymnastics events, representing 10% of the participants. The development of professional competitions attracted the best performing athletes, which prohibited them from taking part in the Olympic Games, which were still only for amateurs, forcing the IOC to remove certain sports from the programme: this was the case of tennis in 1928.

Legende

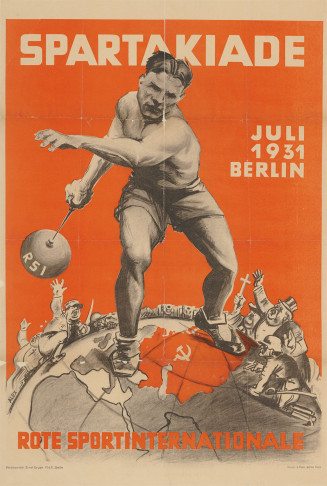

Second Spartakiade (Berlin, 1931), poster signed by Alex and distributed by Rote Sportinternationale, 1930.

Credit

© Archives Nationales

Challenging the bourgeois and worldly Games

The members of the IOC were among the European elite. Some sports, such as sailing, were the preserve of this category of entitled few to which Virginie Herriot, Olympic champion, belonged. Denouncing these “bourgeois sports”, the Communist International organised the Spartakiad in Moscow at the same time as the Amsterdam Games, a reference to Spartacus, the rebellious Roman slave. Four thousand Soviet athletes and 600 foreign athletes from twelve countries tool part in a programme similar to that of the “official” Games.

Ahmed Boughéra El Ouafi, symbol of immigration in France

Enlisted in the French Army, then a worker in the Renault factories at Boulogne-Billancourt, Ahmed Boughéra El Ouafi, French marathon champion, excelled in Amsterdam. A native of Ouled Djellal in southern Algeria, he won the event and the first gold medal for a North African. Despite his win, a lack of money led him to sign a professional agreement to take part in sporting shows in the United States. This excluded him from amateur and Olympic competitions, and he ended his days forgotten and destitute.

Legende

Amsterdam 1928. Ahmed Boughera El Ouafi wins the gold medal in the marathon.

Credit

© Docpix

The economic crisis Games

Legende

View of the rooms in the exhibition Olympism, a world history

Credit

© EPPPD-MNHI

Awarded to Los Angeles since 1923, the organisation of the 1932 Olympic Games proved divisive. In the wake of the financial crash of 1929, American public opinion and President Herbert Hoover considered that hosting the event to be an unjustifiable expense. Doubts expressed by some European athletes about the necessity of holding such an event on the other side of the world added to these reservations. In the end the Games were financed with the help of private capital and the costs of the trip were reduced for participants with the building of an Olympic village - for men only. This was also the first time that the medal award ceremony took place on a podium, with the hoisting of flags and introduction of the national anthem. Magic was weaved in this booming city: the presence of Hollywood stars like Gary Cooper or Buster Keaton added luxury and glamour to the event.

Fascism and imperialism

Coming second among the nations behind the United States, the Italian athletes contributed to the propaganda of fascism. They embodied the “new man” that the totalitarian regime sought to mould, in particular through sport. The rise of forms of nationalism and imperialism in Europe and elsewhere also found an echo in the performance of Japanese athletes, like the rider Nishi Takeichi, an army officer who had just invaded Manchuria (1931).

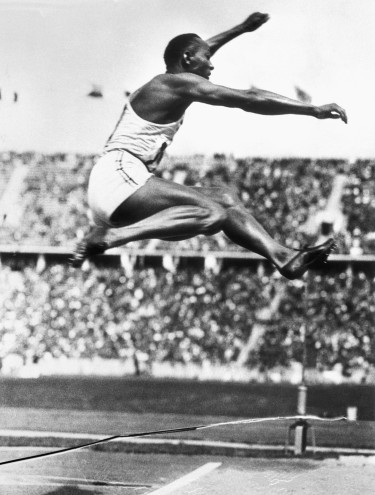

The Hitler Germany Games

Held three years after Adolf Hitler’s election as leader, the Olympic Games in Berlin were a timely opportunity for Nazi regime propaganda. The German leaders maintained the illusion of a “normal country” seeking to erase any trace of anti-Semitism. However, and despite the recommendations pronounced by the IOC, Jewish German athletes were excluded from the competition. Through colossal spending, Berlin organised the biggest sports event ever held. The new, monumental Olympic stadium hosted grandiose ceremonies in a decorum that had multiple references to Antiquity, taken to be one of the basic tenets of Nazi racial ideology. Despite a good performance from German athletes, all eyes were on a black athlete, the African-American sprinter Jesse Owens.

Jesse Owens, running against racism

Jesse Owens won four titles: 100 metres, long jump, 200 metres and 4x100 metre relay. This achievement, which took place before the eyes of Adolf Hitler, discredited the racist theories of the 3rd Reich and the supposed physical superiority of white “Aryans”. The triumph of Owens, the grandson of a slave, contributed to the pride of African-Americans who were still deprived of their civic rights in the American segregationist system. In a break with tradition, he was not invited to the White House on his return from Berlin.

Legende

Berlin Olympic Games (1936) - Jesse Owens in the long jump. In 1936, Jesse Owens won four titles: 100-meter dash, long jump, 200-meter dash and 4x100-meter relay. This feat, achieved in front of Adolf Hitler, discredited the racist theories of the Third Reich.

Credit

© Jesse Owens™ owned and licensed by the Jesse Owens Trust, c/o Luminary Group, www.JesseOwens.com

The People’s Olympiad in Barcelona

When the Nazis reached power in Germany in 1933, it provoked a vast international boycott movement against the Olympic Games planned in Berlin in 1936. The international workers sports movement mobilised to hold alternative Games in Barcelona. Over 6,000 athletes signed up for the People’s Olympiad. The competitions were, however, cancelled because of the start of the civil war that opposed the Spanish Republicans and General Franco’s military junta.

Olympia

The 1936 Games introduced the first relay of the flame carried from Olympia to Berlin. The last runner was captured on camera by filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, who directed Olympia, a feature film honouring the 3rd Reich Games. Using innovative directing and editing, this film offered an aesthetic that would long inspire broadcasters of sports events and influence the cinema. Without eclipsing Jesse Owens’s triumph, Olympia glorifies the antique model of the body, the symbol of “Aryan perfection”.

The cancelled Games of 1940 and 1944

The Second World War was the reason for the cancellation of two consecutive Olympic Games. Tokyo, which should have hosted the 12th Olympics in 1940, eventually decided against holding them because Japan, engaged in an imperialist policy, had entered into a war against China in 1937. The Games were then set for Helsinki, a city that also decided against holding them in 1939 because of the war and the Soviet invasion. The global conflict also prevented the Olympic Games planned for London in 1944 from being held.