5Towards a multi-polar Olympic world (1968-1988)

In the 1970s and 1980s, image strategies and the events surrounding the Olympic Games bore witness to the political and economic emancipation of new nations, as well as the multiplication of international tensions.

In 1972, the Munich Games, supposed to represent a new Germany on the path to reconciliation between East and West, were marred by a terrorist attack carried out as part of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The Games had never taken such a tragic turn. Four years later, in Montreal, the Olympic Games were the subject of the first massive boycott in Olympic history. To oppose the presence of New Zealand, which had hosted the South Africa apartheid rugby team, almost all of the African countries refused to attend. The powerful media echo chamber of the Games was able to draw the attention of an international audience to the struggle against the racist South African system.

The Moscow Olympic Games in 1980 went on to be boycotted by the United States and their allies in protest against the invasion of Afghanistan by the USSR in 1979. Four years later, the USSR and their allies refused to travel to Los Angeles. Against a backdrop of North-South tensions in Korea, the Seoul Games in 1988 paradoxically presaged the end of the Cold War, and heralded an era of global commercialisation of the Olympic Games.

From joy to terror

The 1972 Olympic Games, attributed to Munich, were to erase the memory of the 1936 Games organised by the Nazis. Under the slogan of the “Games of Joy”, the graphic design proclaimed the advent of a modern and democratic West Germany. The first Olympic mascot, Waldi the dachshund came in many versions: stuffed animal, rolling toy, coat rack… The Federal Republic of Germany invested massively to renovate existing infrastructure and build new arenas, like the Olympic Park. On the political stage, Chancellor Willy Brandt considered that the Games should be a means to draw closer to the Democratic German Republic, as part of the Ostpolitik launched in 1969. While recognising the existence of two German States, it sought to normalise their relationship.

Legende

Munich 1972. "Le Carnage", front page of France Soir, September 6, 1972

Credit

© Collection Groupe de recherche Achac

A gold shark: Mark Spitz

Winner of seven gold medals, American swimmer Mark Spitz took his place as the major sports figure of these Games. After disappointing results in Mexico, Mark “The Shark” arrived in Munich with revenge in mind, illustrated by his moustache, which he sported in reaction to the ban on growing one in place at his university. After the attack against the Israeli team, Mark Spitz was escorted out of Germany by his country’s security services, as they feared that his Jewish faith could make him a target.

Death at the Games

The terrorist attack of 5 September 1972, carried out by the Palestinian commando “Black September” against the Israeli delegation, was a stupefying and traumatic event. The death of eleven Israeli athletes provoked an international emotional reaction, further incensed by the decision of the president of the IOC, Avery Brundage, to continue with the competition. His catchphrase “The Games must go on” was perceived as being cynical in the face of the seriousness of the events and a sign of disdain for the victims.

Boycott apartheid!

Since 1963, the voice of recently independent African countries was carried by the Organisation for African Unity (OAU). It fought against the South African regime and its racist apartheid policy. From a sporting point of view, the IOC had excluded South Africa from the Olympic Games for several years, but it did not penalise countries that continued to maintain sports relationships with it. This was the case of New Zealand, which the OAU asked to be excluded from the Montreal Games a few days before they began, threatening a boycott from the organisation’s member countries. Several delegations had already arrived, and the request for New Zealand’s exclusion did not go anywhere, so in the end, 22 African governments insisted that their teams pack their bags and leave without taking part in the events.

A scandalous bill

The Montreal Games cost 1.65 billion dollars, a sum that the City finally paid off thirty years later, in 2007. Some of the expenditure was related to security, which was considerably strengthened after the Munich attack. But above all, Mayor Jean Drapeau wanted to make his city a world capital, with gigantic sporting infrastructure. This ambition was sharply criticised, all the more so because only part of the facilities, built on a scale too vast for a city like Montreal, would continue to be used after the Games.

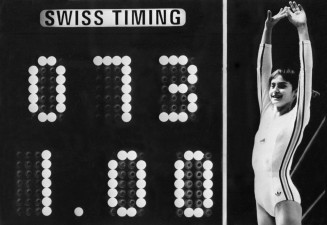

Nadia Comăneci : Perfection under control

At just 14 years old, Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci was the hero of the Montreal Games. She won five medals, including three gold, and she was awarded the first ever perfect score of 10 seven times. As the display was not designed to show such a score, the screen showed 1.0. Strictly controlled and held up as a model by Nicolae Ceaușescu’s dictatorship, which awarded her the “Socialist Work Hero” medal, she opened the way for very young gymnasts to take part in the Olympic Games.

Legende

Montreal Olympic Games (1976) - Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci scores 10/10, a first in Olympic history.

Credit

© AFP

Montreal Olympic Games (1976) - Ethiopian delegation leaving the Olympic Games

© Gabriel Duval / AFP

Two Games, one Cold War

The Moscow Olympic Games in 1980 and the Los Angeles Games in 1984 coincided with the height of the sporting Cold War. This political confrontation was heavily dramatised. As early as 1978, the United States envisaged boycotting the Moscow Games in order to denounce the lack of respect for human rights in the USSR. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 provided the pretext.

In 1984, the Soviets in turn announced, at the last minute, that they would not be taking part in the Los Angeles Olympic Games. Often top of the medal table at the Olympics since 1952, they had every reason to come to California and triumph, but they feared that their athletes would defect to the West.

Opposing economic models were on either side. In Moscow, the Games were organised by the State, investing massively and authorising concession stands to combat the austere image of life in the USSR. 478 shops opened, and many products depicting Misha the bear went on sale. In Los Angeles, the Games were the first to be financed solely by the private sector, and professional athletes were allowed to take part. A demonstration of the strength of the capitalist system, the Los Angeles Games were economically profitable. The opening ceremonies also embodied these strategies. They were both grandiose, the one in Moscow presenting majestic tableaux celebrating the Soviet Union, while those in Los Angeles deployed, in a Hollywood atmosphere, an ode to the American way of life and how the West was won.

Legende

View of the rooms in the exhibition Olympism, a world history

Credit

© EPPPD-MNHI

Neroli Fairhall : A Paralympic and Olympic athlete

Paralysed after an accident, Neroli Fairhall took part in the Paralympic Games in 1972 in several events, without making it to the podium. She went on to choose archery and win a gold medal at the 1980 Paralympic Games. She wanted to take part in the Olympic Games in the same year, but her home country, New Zealand, boycotted them. So, it was in Los Angeles in 1984 that she became the first person with a disability to take part in the Olympic Games after taking part in the Paralympic Games.

Legende

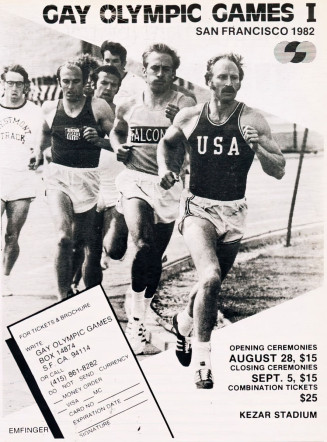

Poster for the first Gay Games, with Tom Waddell, initiator of the movement, in the foreground. 1982

Credit

© Gay Games

The first Gay Games, Games for everyone

The Gay Olympics opened on 28 August 1982 in San Francisco, but the American Olympic committee prohibited the use of the word “Olympic”. In the scramble, they became the Gay Games. Over ten days, the sporting encounters brought together 1,350 athletes from ten countries with no distinction between performance, origin or sex. The idea of their founder, Tom Waddell, who took part in the Games in 1968, was to combat hatred and discrimination against gay and lesbian people.

A gesture that speaks volumes

In Moscow, the Polish athlete Władysław Kozakiewicz won the pole vault competition and broke the world record to beat Soviet athlete Konstantin Volkov. He directed a rude hand gesture towards the crowd, known in French as a bras d’honneur, and the image went around the world. The USSR considered the gesture to be an insult and they asked the IOC to take away his medal. The Polish government refused to penalise the man who was voted Polish sportsman of the year. In the West, this image symbolised the budding protest movement in the Eastern Bloc State.

A victory to open the way

In Los Angeles, when Nawal El Moutawakel won the 400 metres hurdles, she became the first Arab, Muslim and Moroccan woman to win an Olympic gold medal, and a symbol of emancipation. Three years later she became a coach, and then became vice-president of the Moroccan Royal Athletics Federation in 2007. She also embraced a parallel political career. She was first a Secretary of State, then Minister for Youth and Sport from 2007 to 2009, and finally became a member of parliament in 2016.

Proof through Korea

Seoul’s candidacy was supported by the country’s strong economic growth. On the other hand, the political instability of Korea raised some doubts. North Korea viewed the attribution of the Games to the South as an affront, and asked to co-host the event. When negotiations broke down, it announced a boycott and attempted to destabilise its neighbour to the South with an attack that caused a Korean Air flight to blow up in November 1987. The South Korean regime also had to face an internal protest movement demanding democracy and access to essential freedoms. To calm the situation, elections were held that led the country down a democratic and liberal path. The Seoul Olympic Games were placed under the sign of peace and unity, as expressed by the official musical theme.

Legende

View of the rooms in the exhibition Olympism, a world history

Sergueï Bubka : On top of the world

Born in Luhansk in the east of Ukraine, Sergueï Bubka was outstanding for his performances in the pole vault. While he did not take part in the 1984 Games because of the Soviet boycott, he won several international titles and regularly improved the world record, taking it above six metres. At the Seoul Games, he won the gold medal with a 5.9 metre jump. He became an actual worldwide media star under the colours of Ukraine after the USSR was dismantled in 1991, and went on to become a member of the IOC.Ben Johnson : A scandal that opened eyes

Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson caused a sensation when he won the gold medal and broke the world record in the 100 metres, ahead of the star Carl Lewis. Two days later, he was disqualified after a positive anti-doping test. Cases of doping had been revealed at the Olympic Games since tests were put in place in Mexico in 1968, but prior to this, complacency reigned. This time, the media storm caused by the scandal contributed to strengthening sanctions against athletes who took performance enhancing drugs, making them cheats.

Four-legged champion

A horse initially considered to be too small for show jumping and endowed with a difficult personality, Jappeloup de Luze did not initially please French rider Pierre Durand, but he finally decided to become his owner. The pair successfully qualified for the Los Angeles Games, but Jappeloup refused an obstacle and ran away to the stables, leaving his rider on the ground. However, in Seoul four years later, he cleared a majestic flawless round, offering his rider a gold medal. It became a star to rival human athletes.